The term NVIS, or Near Vertical Incidence Skywave is in my short experience as an amateur heaped with scorn and ridicule. Terms like cloud-warmer come to mind when people discuss the principles associated with NVIS, but that does happen in the context of where I live, that is, one of the most isolated cities on the planet, Perth in Western Australia.

NVIS has several advantages over other forms of HF communication, it can be done with low power, there is little or no signal fading, simple antennas work well, it has low path loss, better signal to noise ratios and if you’re in a valley, you can still use it.

So what exactly is NVIS?

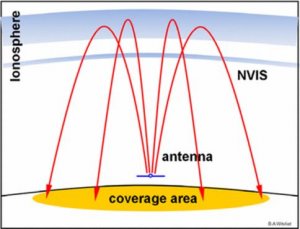

In the past I’ve talked about long distance HF communication. Your radio signal bounces off the ionosphere, bounces back to earth and so-on. Like skipping a stone on a pond, the angle at which your signal hits the ionosphere determines what happens next. In general, shallow is good, steep is bad, much like the plop you hear when you don’t hit the pond just right, a radio signal can go through the ionosphere, never to be heard again.

NVIS is about hitting the ionosphere at a steep angle, in such a way that it reflects back to earth. Without going into detail, generally you can use 40m during the day and 80m at night with some variation depending on the solar cycle and whom you want to talk to.

NVIS gives you communications less than 1000 km away, plenty to talk to everyone in your city and surrounding area. In the case of an emergency that’s also likely enough to get out of any emergency affected area, so plenty of excuses to set up and try for yourself.

I can start talking about angles, maximum usable frequencies and so-on, but I won’t. These all relate to specific circumstances, depend on what antenna you’re using, what the ground conductivity below you is and as is typical in our hobby, many other variables.

What I can say is that NVIS to NVIS station works best, so if you’re going to test this with a friend, it will help if you both set up a similar station while you learn the variation associated with this kind of communications.

Now I did mention up to 1000 km, that isn’t enough to leave Western Australia, Perth to the border is about 1500 km, but if you live in the Netherlands, you can get to 15 or so countries. Depending on where you are, NVIS will give you different outcomes and what I’m talking about affects each station differently.

For me, the attraction of NVIS is solid communications on 40m and 80m, something that has eluded me so far. It also allows for a low simple wire antenna, an inverted vee dipole, two bits of wire strung up on a pole, 6m in the middle 2.5m at the end will get me up and running. Perfect for a field-day, excellent for a local contest and brilliant if you’re only using low power as a beginner.

Because the antenna is close to the ground, it’s pretty much omni-directional. If you set-up an antenna for 40m and then cross that with an 80m antenna and feed them both from the same point, you’ll have a configuration that will operate well for 24 hours without needing to move antennas in the dark.

I have no illusions that an NVIS antenna will help me make contact between Perth and Japan, but then it’s not intended for that. I’ve spoken in the past about finding the right tool for the job. NVIS is a tool, it has a job and it’s very good at doing that. It’s not for everyone, all the time, but it’s a tool that you as an ambitious amateur should know about.

I’m Onno VK6FLAB